Keith Emerson passed away in 2016, having taken his own life. From the outside looking in, this appeared most unlike the bombastic keyboard pioneer captured for posterity on film during his heyday, be that stabbing organs before tipping them on their sides and making them scream out loud across packed arenas, calmly sitting a grand piano to play some classical piece, or producing melodies from Moog synthesiser still as yet unequalled.

An extrovert, if not show-off to the outside looking in. Very possibly so, but as this book captures well, there were very many other sides to the man.

Ostensibly credited to respected veteran music journalist and author Chris Welch, it in fact takes the modern rock biography approach of great snippets of quotes from those who knew or admired the musician. To this, Welch couches a largely historical format into edited narrative informing us of Emerson’s life, onstage and off, and via that involvement of others not just shared war stories to be laughed along to but how his touched their own.

Using classically established musical terminology as chapter headings (and explaining just what those terms mean in subheading) suits the book mostly, though once were engaged as readers such nuances matters little, albeit they’re a conscious decision to be in keeping with the keyboard maestro’s status. Highbrow perhaps, but then one of the things we find through this whistle-stop journey of Emerson’s life is that he struggled with not always being fully accepted as a musician and even more so as a composer, despite many testimonials from the classical, jazz and film world stating for the record otherwise both to him personally within passages of the book.

The use of the word “Illustrated” in the book’s title infers it might be more picture postcard photography filler alongside a few quotes from surviving band members and relatives. Fortunately, such a disservice is not in evidence here. Yes, there are certain publicity, weekly music paper and magazine photos you’ll have seen previously, but the bulk are otherwise, from the candid to lowkey family gatherings, moments caught off guard and beyond. Of two Emerson, Lake & Palmer related matters that really stuck out for me, the one was purely visual – The modern viewpoint expressed tends to be that the three involved were exceptional musicians who gathered to create music, it was formal, more business-like due to professional circumstances rather than social beings collectively, and yet I’m reminded of a comment Roger Daltrey made concerning The Who, where, to paraphrase, he queried why that band had a reputation for always arguing when so many photos showed the four of them smiling. So too with ELP. I guess the problem too often is arguments and bad times kindle our mind more so than the good times that should. If so, look at the upturned lips of progressive rock’s premier trio on the many photos gathered here they tell a story the principal partners possibly couldn’t articulate verbally as time moved on.

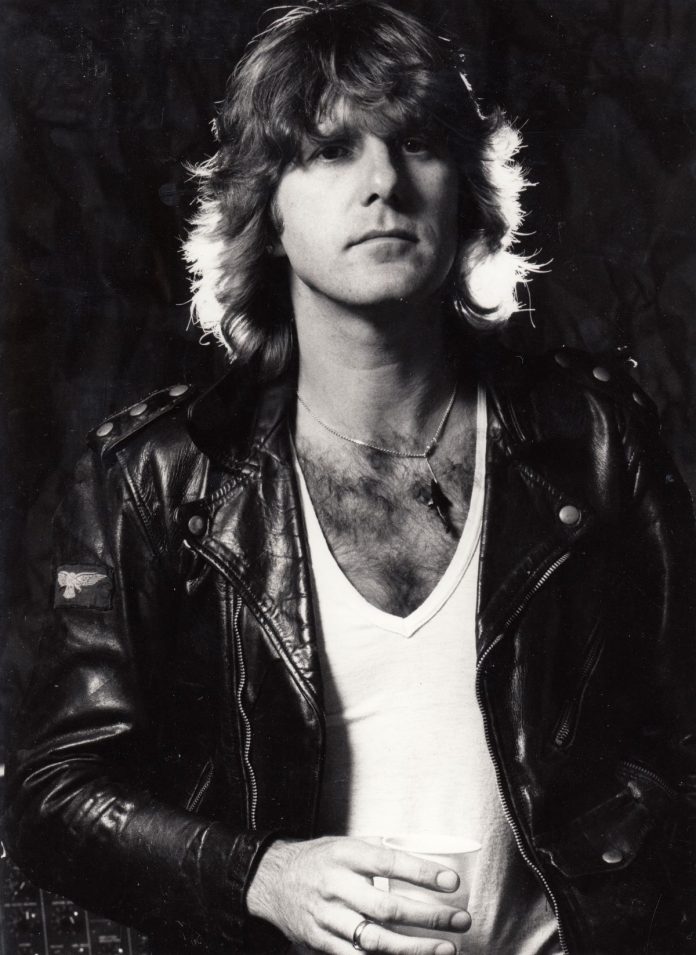

Elsewhere you’ll find Emerson in action, and also that age took a long time to catch up on his face or round the midriff. Inevitably the photos of a short blond-haired lad are produced early, and a mostly happy childhood it was we find, with valuable contributions offered by a close female cousin. That he loved his own children, and doted on grandchildren self-evident also visually, though his nagging concerns of not being there for his sons when long tours beckoned is also noted by the now grown men, who seemed to understand, if only in mature hindsight.

How this hefty collection compares to Keith Emerson’s own autobiography, Pictures Of An Exhibitionist, I’ll leave for others to comment on, though it’s now likely to be on my own Christmas wish list. Rather let’s outline the obvious in that the story begins with the young Keith’s birth, his mutual interests in music, photography, and to some degree sports (this more outgoing aspect of his personality would continue in latter-life, with such adventure sports as skiing), close family associations and certain friends who remained through much of his life.

With his childhood established, and no boogie men fingered ready to be prepare us for Freudian pop psychology further down the line, things move briskly with him joining assorted early bands, most pivotally when he played with The V.I.P.s – But a brief time in his extensive career, but I remain intrigued by this period, for that band became the more established Spooky Tooth, with various members splintering off to join bands of all genres. From there we move to the formation of P.P. Arnold’s backing band, and in its turn The Nice, where it can be argued the psychedelic soul and underground political leanings that are usually attributed to being developments and contributing factors in creative the progressive rock scene, took second place to the influence of European classical music. Of course, such factors are all well-established, but bass player Lee Jackson’s comments round things out more suitably.

The stage now set, lengthy entries on Keith Emerson, Greg Lake and Carl Palmer’s coming together, conquering all they saw before them, their subsequent freefall from popularity (with the subjects of employing orchestras and the rise of punk given voice), and assorted reunions and rumours of such for all three key members or side projects with one or other joining Emerson, taking a large chunk thereafter.

Between The Nice and ELP, there is much input from Emerson’s first wife. If there is a gap in the historic narrative, and possibly understandably so, it’s that we’re never quite sure when or why the marriage breaks at first, simply picking up on it as a new female character starts to take precedence in relating events. Despite this, and us latterly finding there was some acrimony when the first marriage broke, there is genuine fondness expressed of times spent together before the marriage went sour and as the world opened up with all the financial rewards that it offered. Business managers, personal assistants and similar also offer input into Emerson’s personality here, generally he’s easy to get along with, but two factors come to the fore: that he suffered from stage-fright, an obvious, and the mental strain of psyching himself up was possibly unleashed in his exuberant actual performances once standing beside his mad scientist potpourri of keyboards (Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham, a legendary rock madman, himself admitted to often vomiting before being able to go on stage). More than nerves about performing live, was the fear of not being able to be good enough, and once he’d made his name, living up to his reputation… As time progressed, he would suffer very real problems with his hands, operations did not help. This continuing deterioration of his most precious tools is what persisted in haunting him, and we must assume ultimately drove him to the point of no return.

At one point alcohol is used as a crutch, and friends found in the most unlikely of places. Down the years I’ve read the odd snidey comment about Greg Lake, notably credited in print to Emerson, but it is he who offers Emerson a safe haven from the pressure and despair he’s suffering, the Lake family giving him a place to hide away from it all in their own palatial mansion.

Latterly, we find Emerson living mainly in the USA, writing film music, playing with pick-up all star bands for odd tours but nothing ever very concrete. Not until he began re-establishing himself on British shores, reforming The Nice, and latterly ELP, and solo, all while giving what appeared much happy talk in magazine interviews. Alas, we all put on a face.

While there’s a sad tragic end to this story, it doesn’t mean it’s a depressing read, far from it and among the laughs to be had you can be assured that Rick Wakeman doesn’t let the reader down.

Likewise, many are the anecdotes from comedians and cousins alike of Emerson vanishing from a party or waking up in the middle of the night, lost in thought composing and in need of a piano to express himself. That many of those unrecorded pieces were written down, and might one day be heard on whatever future recording devices the world has, played by his talented grandson is something fans might want to say a little prayer for.

That one of the latter chapters is given over to his actual keyboards may be a little dry for some but it’s not overly long, with people explaining details about them, and sundry photos for the keyboard fetishist, while it’s duly noted the family has donated them to museums is only right.

The faults are few here. It doesn’t cover over many cracks, albeit you go in knowing this is intended to celebrate not be a hatchet job. It’s one of the best designed rock books I’ve seen in a very long time, no make that one of the best designed books of any kind I’ve seen in a long time. It’s a coffee table book because you not only want to show it off (great pics and all) but because you want to share assorted yarns from it with friends.

Strangely, while I’m listening to ELP’s Trilogy album as I type these final comments, what was foremost on my mind while reading this book was Emerson’s live appearance on Oscar Peterson Invites a show that appeared on ITV on Sundays; the pair sat at grand pianos facing each other playing some super cool jazz. My late father-in-law was a semi-pro jazz keyboard player, Peterson being his major influence, and if that made me think of him too, that’s just another good thing I got out of this book.

Keith Emerson: The Official Illustrated Story by Chris Welch is available to purchase by clicking here.