The blues are not always blue, but sometimes they are the darkest shade of midnight. Larry Griffith grew up the youngest of ten children in a single-parent household. His father died when he was two, and his mother struggled to support the family on the wages of a domestic worker. The neighbourhood they could afford to live was dangerous: gunshots outside his home were a regular occurrence, and he even remembers seeing someone stabbed to death.

In that midnight sky, the stars that shone for him were words – words in books, of people like Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and William Faulkner, and in the lyrics of the folk and jazz music his mother loved. As a 9-year-old, he would copy down words from the songs he felt drawn in those that touched him, as varied as Billy Strayhorn and Bob Dylan. Like a series of John Coltrane phrases, words and music swooped him again and again out of his immediate world and into a better one: “Music elevated me,” he says.

As he got older, he learned to drum and do it well, and music elevated him another way – with his peers – whose respect was not so easy to attain, especially for a boy who preferred reading over rowdiness. But mostly it was the words, and when he realized that he could change the world for his listeners, elevating them with his own words if even for just a few moments, he knew what he wanted to do with his life. It wasn’t a calling, per se; It was a necessity, because, he found, in elevating others, that he elevated himself even more.

Larry eventually became a studio drummer, learned to sing and play the guitar, and eventually served in a number of different roles in the music business: recording, arranging, producing, publishing, and writing for others. He also learned how to entertain audiences whom, he says, “hear with their eyes”. In a time and place where many musicians are struggling to find work, he maintains a busy schedule. He says “I don’t really believe much in luck. I work hard to be able to do nothing but music”. Yet at the same time, he doesn’t push the creative process or try too hard to spin records into gold. And, it always came back to the words.

Words explain why he was particularly drawn Willie Dixon’s music, whom he calls “the “greatest songwriter that the blues has ever had…Nobody tells a better story than Willie Dixon or a has a better, clearer melody,”. And when Larry writes a song, he doesn’t start with a guitar lick or drum rhythm. He gives the words center stage: “I tell a story through the lyric, then dress up that lyric with music.”

The “swiss army knife of blues players”

This explains why he doesn’t limit himself to just one style – why one journalist called him the “swiss army knife of blues players.” Indeed, his work ranges from the more primitive sounds of the early blues pioneers in ‘Damn if it Didn’t Rain’ to the Southern rock R & B grooves of ‘Had Enough‘ and includes most everything in between. It’s truth and meaning that Larry is after, and whatever style best augments the story he’s telling is the style he goes with.

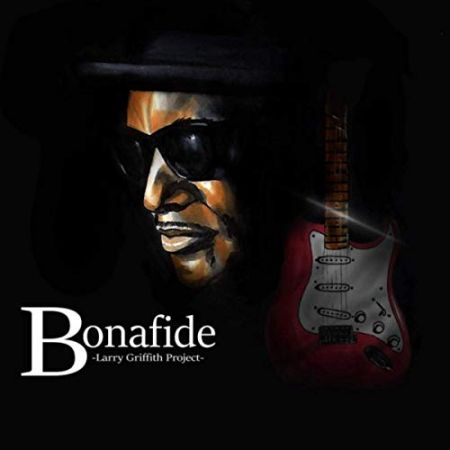

His latest album, Bonafide, showcases this musical versatility while exemplifying what the blues is all about. It’s a semi-autobiographical stream of struggle, hope, and joy, both in his early life (‘Mama Tried’) and through a relationship gone south- beginning with dangerous attraction (‘Hoodoo Hannah’) and ending with the farrago of emotions that accompany leaving something that’s no longer working (‘I Know’; It’s Always Going to Be Something With You’; ‘I Do, I Did, I’m Done’; ‘Had Enough’, and, finally, ‘I’m Free’). Griffith explains that his songs are about how “the rainbow’s gonna give away to rain and the rain’s gonna give away to the rainbow.” But, also, he says, there is “just a little bit of humour in even the darkest thing,” and he weaves in some levity with ‘Slow Grind’, a song which, if it doesn’t make you blush, wlll have you laughing (or speaking Japanese).

Arguably, the best song on the album is ‘It Ain’t What They Call You’, in which the upbeat tempo matches the message Larry has lived of rising above other people’s expectations (or lack thereof) and false perceptions. It is in this song, his life purpose of lifting others while lifting himself is most apparent. Bonafide additionally features guitarist Barry Richman, who gilds the lily with beautifully toned fills that range in colour from aquamarine to indigo.

“The song is the star, not whoever is singing”

But while Larry’s versatility is fully apparent on the album, it always seems to come back to the blues. Larry is bothered by some young people who call themselves blues musicians, yet don’t seem to get what it’s all about: “The song is the star, not whoever is singing – [the blues] is not about a guitar whacking off – it’s not about that”, he says. The place you need to learn to play the blues is not on stage. You have to sit in the darkness and find the light in yourself. The blues, he says, is “the beautiful angel child and the soul of the tortured artist.”

So, how does one become a true blues artist? It begins with words – the glue between human beings that allow us to share suffering and to encourage each other with visions of better things. Words work like alchemists to transform straw into gold – pain into hope, then survival, and finally celebration. And where words no longer suffice, there is music. Perhaps the blues knows this more than any other genre – like all beautiful things, it, too, was born of suffering and joy.

“Tell it, tell it, tell it,” Larry says in one song. And he does: “I feel like you arrive when you feel like you find what you are supposed to be doing with your life… I know who I am I know what I want to do. I’m already where I want to be. My whole dream is to do what I love and to make a living at it.”

Larry’s CD’s are available for purchase via this site, and many songs are available for download on Spotify and Soundcloud, among other streaming services: http://www.larrygriffithmusic.com