John Martyn was a walking contradiction, even when he lost a leg. That he made music so beautiful and so full of anger, sometimes in the same song, proved this. What we thought we knew about him changed somewhat after he died: he wasn’t born in Scotland, the name he sang under wasn’t his real one, and pretty much everything else is supposition, gossip and hearsay. That he received a posthumous OBE would probably have made him laugh like a madman.

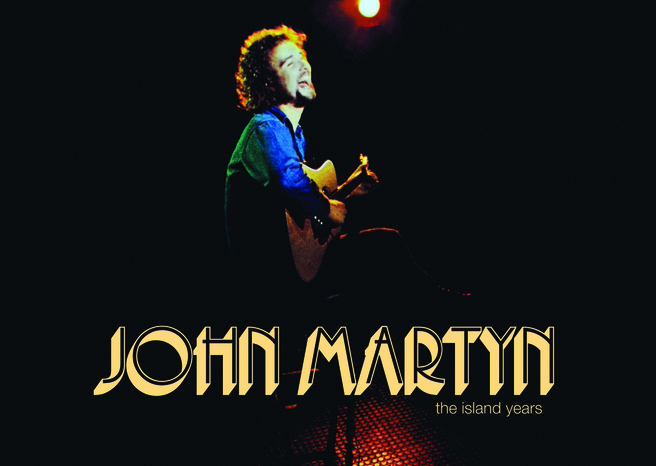

Martyn burst onto the late 60s music scene with his acoustic guitar singing folk and some blues, traditional for the most part but ever edging his bets. He signed to Island Records who fostered and nurtured his talent, and that couldn’t have been easy for the music he played – if not the man himself – changed several times and it’s not easy to promote that kind of thing. In his later life the hoi polloi of the fashionable music scene made efforts to have him as part of their inner circle (probably because having taken the late Nick Drake to their bosom finding the title track to Martyn’s classic Solid Air album was about him made him more appealing). It’s no doubt what’s lead to an epic 18 volume collection of his work, featuring albums from his debut London Calling to Piece by Piece, countless live tracks from all periods, DVDs, four songs never heard before, a 120 page hard back book, press kit, 1978 tour programme and poster – You will also not be surprised that this is only available in a limited edition format.

A n expensive experience for the uninitiated, but worth more than its weight in gold for those who’ve previously fell under Martyn’s spell. His early albums fell into the traditional folk scene sound of the times, alongside some acoustic blues, and collaborations with his then-wife Beverley, most notably on Stormbringer. But changes slipped in; initially it was his vocal approach wherein it began to approximate the slurring effect produced by jazz saxophonists, that at times it also had the affectation of coming across like a drunken Scottish hooligan singing love songs worked wonderfully as a marketing tool, and may well have had some truth in at times. He started putting his acoustic through effects pedals, most notably an Echoplex, becoming a one man avant garde orchestra, and some now claim that in doing so he invented trip hop. But that was in hindsight, for with stand up jazz bass player Danny Thompon by his side when playing live they were heading out into what were then experimental progressive areas, despite which Martyn was always able to pull back into the song and tell a story. Disc Five – Live at the Hanging Lamp – Richmond – 8th may 1972 will indeed be an important recording of this transitional period in his musical career featuring tracks from Bless the Weather and what would become Solid Air – The fact that a song could at once be familiar to his audience but change in approach over the years, and probably between gigs was of paramount importance, from the sampling of this collection offered me there are two versions of that very song , the first being the studio version coloured by keyboards and punctuated loosely by Thompson’s bass, the later from Live at Leeds where Martyn’s guitar and voice play more on the beat.

n expensive experience for the uninitiated, but worth more than its weight in gold for those who’ve previously fell under Martyn’s spell. His early albums fell into the traditional folk scene sound of the times, alongside some acoustic blues, and collaborations with his then-wife Beverley, most notably on Stormbringer. But changes slipped in; initially it was his vocal approach wherein it began to approximate the slurring effect produced by jazz saxophonists, that at times it also had the affectation of coming across like a drunken Scottish hooligan singing love songs worked wonderfully as a marketing tool, and may well have had some truth in at times. He started putting his acoustic through effects pedals, most notably an Echoplex, becoming a one man avant garde orchestra, and some now claim that in doing so he invented trip hop. But that was in hindsight, for with stand up jazz bass player Danny Thompon by his side when playing live they were heading out into what were then experimental progressive areas, despite which Martyn was always able to pull back into the song and tell a story. Disc Five – Live at the Hanging Lamp – Richmond – 8th may 1972 will indeed be an important recording of this transitional period in his musical career featuring tracks from Bless the Weather and what would become Solid Air – The fact that a song could at once be familiar to his audience but change in approach over the years, and probably between gigs was of paramount importance, from the sampling of this collection offered me there are two versions of that very song , the first being the studio version coloured by keyboards and punctuated loosely by Thompson’s bass, the later from Live at Leeds where Martyn’s guitar and voice play more on the beat.

The importance of 1973’s Solid Air cannot be understated for the bulk of the songs continued to be played live by the man during his career, from the upbeat tale of life’s journey to be enjoyed on Over the Hill to the vicious harrowing blues of I’d Rather Be the Devil and the troubadour’s love song of May You Never, a relatively simply acoustic number sung with affectionate passion that I was grateful my better half was thrilled to see him perform live herself later in his career.

For me, it was One World whereby I became enthralled for a good long time by Martyn’s work. The slow title track may have old hippy love and peace lyrics but they come straight after the opening Dealer, that would become a monster when played with a band – its cascading echoed guitar sounds ever building as the song turns from one that can be misinterpreted as being about romance to a full blown drugs problem, the initial lullaby hook line of “Let me in, sweet darling” ended up as a menacing musical equivalent of Jack Nicholson in The Shining. Martyn’s home life was apparently not sweetness and light back then, but the near-prog joyous jig of the Radio 1 played single Dancing barely hints at such dark deeds behind closed doors, excusing himself as he does in the lyrics “the boys wouldn’t let me run away” for staying out drinking all night. But there is also, Couldn’t Love You More, over which there can no question of its poetical concerns; it is simply magnificent, heartfelt, driven with passion, and delivered with a husky, at times near sobbing, vocal quality that all cover versions (including another version by the man himself) have failed to achieve.

For John Martyn himself, Grace & Danger was his crowning glory. Its title says everything one really ought to know about the man, equals parts gentleman and savage hooligan. That it documents his divorce from Beverley Martyn, and as such is a pre-cursor to Phil Collins’s own divorcee album debut, Face Value, cannot be dismissed – Collins would in fact play drums and backing vocals on the album, and later produce the Glorious Fool album made for WEA. Lyrically, as always, Martyn laid the cards on the table before you to tell you what was going on in his life, musically it has much more muscle, not least through Collins’ drumming (people tend to forget he knows how to bash a kit about) but with Brand X’s John Giblin on bass too, all this being proven in the title track, the rock reggae of Johnny Too Bad and others, but still there were bittersweet painful love songs like Hurt in Your Heart.

From this period he would form a protective musical nucleus around him, predominantly jazz rock in approach, with bass guitarist Alan Thomson replacing the similarly named Danny as his live counterfoil: the seated acoustic effects driven player of his youth had been replaced by a snazzy-dressed electric guitarist and the sight of him and Thomson bobbing and weaving around a stage, lost in the music was something to behold. And with the gifted talents of Max Middleton on keyboards it added to the creativity of older songs like Sunday’s Child at the same time as increasing the heavy duty sound of songs like Big Muff (named after the distortion pedal). Jazz rock has a tendency to blur into complicated noise for those not into it, but that it was a style applied to Martyn’s skilfully crafted songs is important to remember. Yes, the direction did become more staid but at their creative best this was a band to witness live, and it looks like a good number of the tracks featured over this collection feature them.

On record though, Martyn began playing understudy to the style of music that was making Collins popular as a solo artist. Slicker, soul-drenched works; the roar and anguish in his voice perfect as sheer expressions of emotion, but the songs themselves fine as background music in some modern Richard Curtis movie are lacking for the most part. Even so, the singular anger, defiance and, yes, self-mythology that bursts through on a track like Piece by Piece’s John Wayne, where simply evoking the giant actor’s name repeatedly or adding “I am John Wayne” gives us a very clear picture of the image he wanted his public to see at the time. He had a top 30 record with Well Kept Secret but people began to stop buying those records; having lost Island as a label he would also begin to forgo his band, playing acoustic in clubs and puns up and down the UK, back to his roots yet without apparent despair. Building up from the grassroots again, I got to see him triumph at Birmingham’s Town Hall, thereafter it seems experimental trip-hop soundscapes and jazzier voiced songs were the direction he went in that accorded him attention prior to latterday TV celebrations, and his unfortunate death in 2009.

John Martyn was never just a folk singer with an honest song to sing; he always experimented even if it lead him down a musical cul de sac; when he rocked live, his sweating hairy face could make most heavy metal merchants wet themselves, similarly hard hearts could melt over o ne of his love songs, out-there reggae types and progressive rock musicians alike played on his albums.

ne of his love songs, out-there reggae types and progressive rock musicians alike played on his albums.

For the most part, his Island days cannot be viewed as anything other than a golden time under the sun, and there were ruby and emerald encrusted periods within those too. Together with rare live recordings, and full sets from those Old Grey Whistle Test shows we’ve all now seen clips of repeated on TV, John Martyn – The Island Years – Limited Edition Box Set is an undertaking that should be applauded, I trust those purchasing copies will not just have them for show but actually play them – John Martyn was a complex person who sung of the human experience and we are blessed that his records can still be heard to inform us we are not alone in having similar foibles, insecurities, gross conceits while also being able to know great joy and forgiveness ourselves.

JOHN MARTYN ‘The Island Years‘ is an 18 Disc Box Set, released via Universal Music, on September 30th 2013.